☆ Yσɠƚԋσʂ ☆

- 4.96K Posts

- 6.41K Comments

2·5 hours ago

2·5 hours agoseems they have kernels on github, but I haven’t looked too closely https://github.com/onyx-intl/Kernel_BOOX60

10·11 hours ago

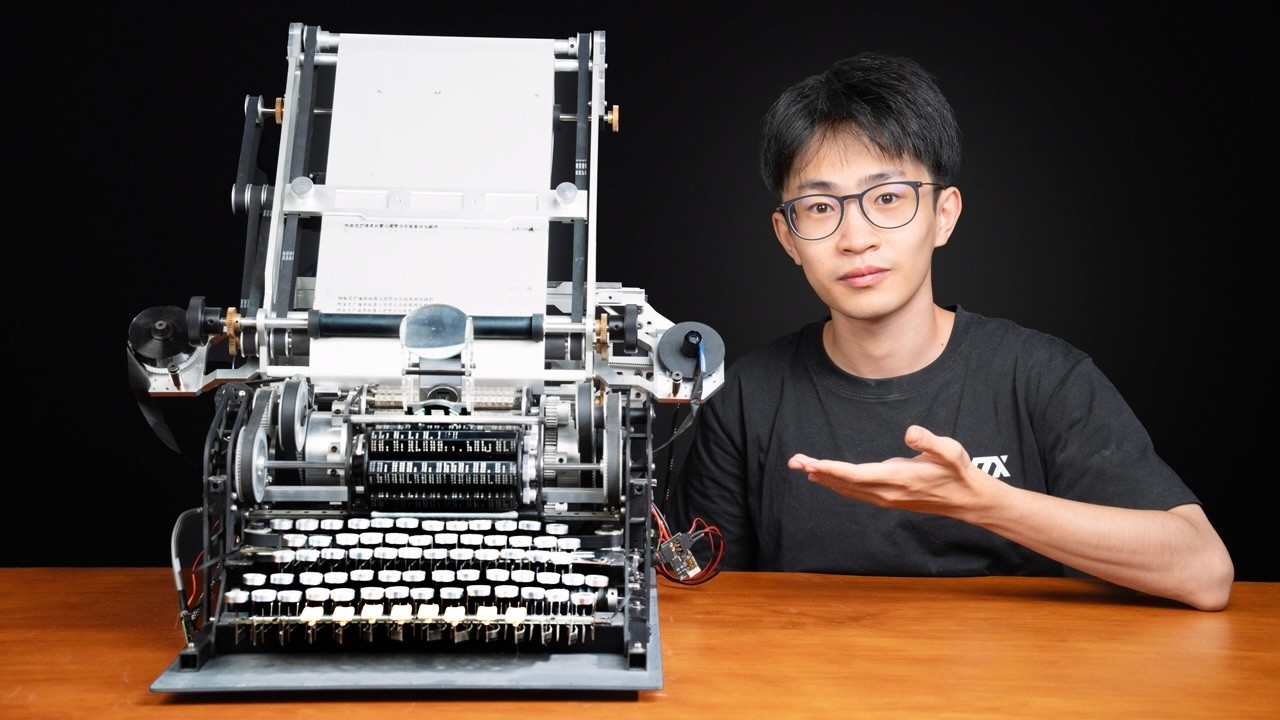

10·11 hours agoA BOOX device is basically an Android tablet with an eye-friendly e-ink screen. The nice part is that you can install whatever book store you want on it, you can get the Kindle, the Kobo, Libby for library books, Moon+ Reader, or any other reading app you want. You’re not locked into one ecosystem.

The other thing is that BOOX devices are for writing and productivity, not just reading. They have stylus support and fantastic note-taking apps built in. So you can mark up a PDF, take meeting notes, or split the screen to have a book open on one side and your notes on the other.

So, while a typical ebook vendor gives you a closed device to consume their content, BOOX gives you an open, flexible tool that you can use anyway you like.

a lost redditor appears

0·1 day ago

0·1 day agoShe explains the problem very eloquently. The whole thing with people wanting to live in a black and white world is really maddening. The behavior she’s describing also shows that many people have an infantile level of intellectual development where they can’t deal with complex topics like actual adults.

3·1 day ago

3·1 day agoyeah, Xiaomi have their own HyperOS now

1·1 day ago

1·1 day agothe problem is the app ecosystem

1·5 days ago

1·5 days agosame in Canada, it’s really frustrating that my only options are Google or Apple

5·7 days ago

5·7 days agoExactly, you can have the train station downtown so you don’t have to get to the airport, wait for checkin, wait for the plane, etc. If you factor all the time around the trip, 6 hour train ride will win every time.

4·9 days ago

4·9 days agoRight, it’s the systemic pressures of capitalism that tend to select for a certain type of behavior. It’s what Cory Doctorow terms enshittification. The key part to keep in mind is that selection pressures guide general behavior within the system, it’s perfectly possible for outliers to exist. However, it doesn’t mean they will continue to be good actors. For example, telegram has already been adding ads in channels, and there will probably be more dark patterns going forward if it manages to secure a big enough chunk of the market. It’s also hard to say what will happen with Valve once Gabe steps away from it.

1·9 days ago

1·9 days agoI’m guessing you didn’t bother actually reading the paper, here are some relevant quotes from it:

This paper compares an example implementation from the RISC and CISC architectural schools (a MIPS M/2000 and a Digital VAX 8700) on nine of the ten SPEC benchmarks.

Performance comparisons across different computer architectures cannot usually separate the architectural contribution from various implementation and technology contributions to performance.

We will do this by studying two machines, one from each architectural school, that are strikingly similar in hardware organization, albeit quite different in technology and cost.

There are strong organizational similarities between the VAX 8700 and the MIPS M/2000… Figure 1 shows that the pipelines match up quite closely, with the obvious exception of the VAX instruction decode stage.

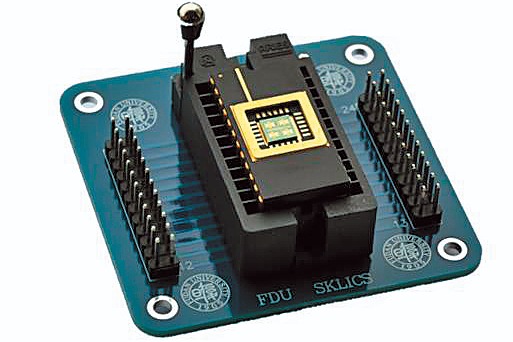

…these two machines are very different in technology, size, and cost: the VAX processor is nine boards full of ECL gate arrays; the MIPS processor is one board with two custom CMOS chips.

…this paper shows that the resulting advantage in cycles per program ranges from slightly under a factor of 2 to almost a factor of 4, with a geometric mean of 2.7.

This factor [the RISC factor] ranges from just under 2 to just under 4, with a geometric mean of 2.66.

The RISC approach offers, compared with VAX, many fewer cycles per instruction but somewhat more instructions per program.

The correlation has a simple and natural explanation: given reasonable compilers, higher VAX CPI should correspond to a higher relative instruction count on MIPS.

The MIPS architecture has 32 (32-bit wide) general registers and 16 (64-bit wide) floating-point registers; VAX has 15 (32-bit wide) general registers… This can obviously lead to more memory references on the VAX…

The time for the simplest taken branch (or unconditional jump) on the VAX 8700 is five cycles. On MIPS, which has a delayed branch, it is one cycle if the delay slot is filled, and two otherwise.

The MIPS architecture allows instructions to be inserted in code positions that might otherwise be lost to pipeline delays… This ability is not present in the VAX architecture…

First, we cannot easily disentangle the influence of the compiler from the influence of the architecture. Thus, strictly speaking, our results do not compare the VAX and MIPS architectures per se, but rather the combination of architecture with compiler.

Second, we measured a rather small number of programs. Measurements that attempt to characterize machines broadly should be based on much more data.

…we believe that the fundamental finding will stand up: from the architectural point of view (that is, neglecting cycle time), RISC as exemplified by MIPS offers a significant processor performance advantage over a VAX of comparable hardware organization.

31·9 days ago

31·9 days agoLikely the ones you’re hallucinating.

23·10 days ago

23·10 days agoYou should only use models that are safely and reliably tuned to spew capitalist talking points.

19·10 days ago

19·10 days agoIt’s hilarious how they can’t complain that the model is controlled by evil see see pee since it’s open, so they’re now complaining that users being able to tune it the way they like is somehow nefarious. What happened to all the freeze peach we were promised.

9·10 days ago

9·10 days agoPublic forums should be publicly owned. These are essential social tools that allow us to have discussions with each other and shape our views and opinions. These forums must be operated in an open and transparent manner in a way that’s accountable to the public.

Privately owned platforms are neither neutral or unbiased. The content on these sites is carefully curated. Views and opinions that are unpalatable to the owners of these platforms are often suppressed, and sometimes outright banned. When the content that a user produces does not fit with the interests of the platform it gets removed and communities end up being destroyed.

Another problem is that user data constitutes a significant source of revenue for corporate social media platforms. The information collected about the users can reveal a lot more about the individual than most people realize. It’s possible for the owners of the platforms to identify users based on the address of the device they’re using, see their location, who they interact with, and so on. This creates a comprehensive profile of the person along with the network of individuals whom they interact with.

This information is shared with the affiliates of the platform as well as government entities. It’s clear that commercial platforms do not respect user privacy, nor are the users in control of their content. While it can be useful to participate on such platforms in order to agitate, educate, and recruit comrades, they should not be seen as open forums.

Open source platforms provide a viable alternative to corporate social media. These platforms are developed on a non-profit basis and are hosted by volunteers across the globe. A growing number of such platforms are available today and millions of people are using them already.

From that perspective I think that open and federated platforms. Instead of all users having accounts on the same server, federated platforms have many servers that all talk to each other to create the network. If you have the technical expertise, it’s even possible to run your own.

One important aspect of the Fediverse is that it’s much harder to censor and manipulate content than it is with centralized networks such as Reddit and BlueSky. There is no single company deciding what content can go on the network, and servers are hosted by regular people across many different countries and jurisdictions.

Open platforms explicitly avoid tracking users and collecting their data. It’s also more difficult for third parties to collect data since it doesn’t all conveniently live on the same server that some company owns. Not only are these platforms better at respecting user privacy, they also tend to provide a better user experience without annoying ads and tracker bloat.

Another interesting aspect of the Fediverse is that it promotes collaboration. Traditional commercial platforms like Facebook or Youtube have no incentive to allow users to move data between them. They directly compete for users in a zero sum game and go out of their way to make it difficult to share content across them. This is the reason we often see screenshots from one site being posted on another.

On the other hand, a federated network that’s developed in the open and largely hosted non-profit results in a positive-sum game environment. Users joining any of the platforms on the network help grow the entire network. More users joining Mastodon is a net positive for Lemmy because we get more content and more people to have discussions with.

Having many different sites hosted by individuals was the way the internet was intended to work in the first place, it’s actually quite impressive how corporations took the open network of the internet and managed to turn it into a series of walled gardens.

Marxist theory states that in order to be free, the workers must own the means of production. This idea is directly applicable in the context of social media. Only when we own the platforms that we use will we be free to post our thoughts and ideas without having to worry about them being censored by corporate interests.

No matter how great a commercial platform might be, sooner or later it’s going to either disappear or change in a way that doesn’t suit you because companies must constantly chase profit in order to survive. This is a bad situation to be in as a user since you have little control over the evolution of a platform.

On the other hand, open source has a very different dynamic. Projects can survive with little or no commercial incentive because they’re developed by people who themselves benefit from their work. Projects can also be easily forked and taken in different directions by different groups of users if there is a disagreement regarding the direction of the platform. Even when projects become abandoned, they can be picked up again by new teams as long as there is an interested community of users around them.

It’s time for us to get serious about owning our tools and start using communication platforms built by the people and for the people.

20·10 days ago

20·10 days agoJust look at Europe at the start of the 20th century and the rise of fascism. We’re seeing a very similar dynamic unfolding in the west today. It lasted until USSR broke the back of the fascists in WW2. It’s also important to note that right wing extremism gets a lot of support from the rich normalizing their views.

It’s also dangerous to think that such right wing movement can be stopped simply by voting. German nazis never won more than 37% of the vote while there were still democratic elections in place. Once these people get in power the mask comes off.

First chapter in Blackshirts and Reds discusses the rise of fascists in Italy and nazis in Germany, and it’s hard not to draw parallels with what we’re seeing happening across the Western sphere right now:

After World War I, Italy had settled into a pattern of parliamentary democracy. The low pay scales were improving, and the trains were already running on time. But the capitalist economy was in a postwar recession. Investments stagnated, heavy industry operated far below capacity, and corporate profits and agribusiness exports were declining.

To maintain profit levels, the large landowners and industrialists would have to slash wages and raise prices. The state in turn would have to provide them with massive subsidies and tax exemptions. To finance this corporate welfarism, the populace would have to be taxed more heavily, and social services and welfare expenditures would have to be drastically cut - measures that might sound familiar to us today. But the government was not completely free to pursue this course. By 1921 , many Italian workers and peasants were unionized and had their own political organizations. With demonstrations, strikes, boycotts, factory takeovers, and the forceable occupation of farmlands, they had won the right to organize, along with concessions in wages and work conditions.

To impose a full measure of austerity upon workers and peasants, the ruling economic interests would have to abolish the democratic rights that helped the masses defend their modest living standards. The solution was to smash their unions, political organizations, and civil liberties. Industrialists and big landowners wanted someone at the helm who could break the power of organized workers and farm laborers and impose a stern order on the masses. For this task Benito Mussolini, armed with his gangs of Blackshirts, seemed the likely candidate.

In 1922, the Federazione Industriale, composed of the leaders of industry, along with representatives from the banking and agribusiness associations, met with Mussolini to plan the “March on Rome,” contributing 20 million lire to the undertaking. With the additional backing of Italy’s top military officers and police chiefs, the fascist “revolution”- really a coup d’etat - took place.

In Germany, a similar pattern of complicity between fascists and capitalists emerged. German workers and farm laborers had won the right to unionize, the eight-hour day, and unemployment insurance. But to revive profit levels, heavy industry and big finance wanted wage cuts for their workers and massive state subsidies and tax cuts for themselves.

During the 1920s, the Nazi Sturmabteilung or SA, the brown shirted storm troopers, subsidized by business, were used mostly as an antilabor paramilitary force whose function was to terrorize workers and farm laborers. By 1930, most of the tycoons had concluded that the Weimar Republic no longer served their needs and was too accommodating to the working class. They greatly increased their subsidies to Hitler, propelling the Nazi party onto the national stage. Business tycoons supplied the Nazis with generous funds for fleets of motor cars and loudspeakers to saturate the cities and villages of Germany, along with funds for Nazi party organizations, youth groups, and paramilitary forces. In the July 1932 campaign, Hitler had sufficient funds to fly to fifty cities in the last two weeks alone.

In that same campaign the Nazis received 37.3 percent of the vote, the highest they ever won in a democratic national election. They never had a majority of the people on their side. To the extent that they had any kind of reliable base, it generally was among the more affluent members of society. In addition, elements of the petty bourgeoisie and many lumpenproletariats served as strong-arm party thugs, organized into the SA storm troopers. But the great majority of the organized working class supported the Communists or Social Democrats to the very end.

In the December 1932 election, three candidates ran for president: the conservative incumbent Field Marshal von Hindenburg, the Nazi candidate Adolph Hitler, and the Communist party candidate Ernst Thaelmann. In his campaign, Thaelmann argued that a vote for Hindenburg amounted to a vote for Hitler and that Hitler would lead Germany into war. The bourgeois press, including the Social Democrats, denounced this view as “Moscow inspired.” Hindenburg was re-elected while the Nazis dropped approximately two million votes in the Reichstag election as compared to their peak of over 13.7 million.

True to form, the Social Democrat leaders refused the Communist party’s proposal to form an eleventh-hour coalition against Nazism. As in many other countries past and present, so in Germany, the Social Democrats would sooner ally themselves with the reactionary Right than make common cause with the Reds. Meanwhile a number of right-wing parties coalesced behind the Nazis and in January 1933, just weeks after the election, Hindenburg invited Hitler to become chancellor.

8·12 days ago

8·12 days agoso your actual problem is with capitalism as opposed to the tech itself

yeah that’s unfortunate then